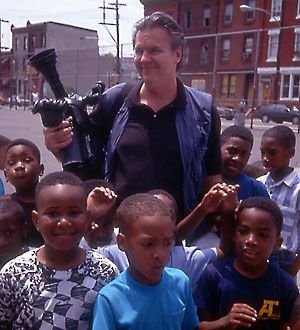

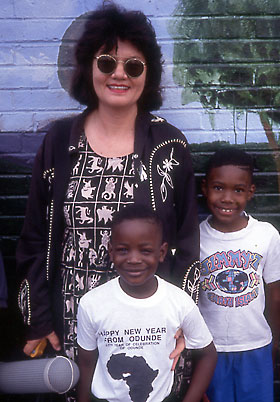

I AM A PROMISESpeech given by Alan Raymond at the Academy of Arts and Sciences  "As documentary filmmakers, we’ve always been interested in children’s issues, especially those children whose lives are in crisis. We’ve documented children living in international war zones and also those growing up outside the American dream. In the early 1990’s, we envisioned producing a documentary on minority education centered on an urban school located in a high poverty neighborhood. The initial idea was to portray the struggles of African American teenagers in an inner city high school but after much thought, we decided instead to go younger in age and focus on elementary school children. Part of our reasoning for this was that these children were the most vulnerable, growing up in an at risk environment of poverty, single parent homes and a widespread drug culture. Since we’re based on the East Coast, we decided to make the film in Philadelphia. The city seemed pretty typical in terms of its demographics and mix of middle class and high poverty neighborhoods. When first meeting with the media relations people at the Philadelphia School District, We were told that they had a previous bad experience with a documentary filmmaker named Wiseman who had made a film at Philadelphia’s Northwest High School. It should be noted that “High School” had been made in 1968 and this was 1992. Staring us coldly in the face, they wanted to know if we were anything like him. After reassuring the media people with the straightest face possible that our film making style was nothing at all like Wiseman’s, we were granted permission to visit a number of elementary schools in the city. Staying at a center city hotel, our first unsettling experience was that cab drivers refused to take us to the neighborhoods where the schools were located. Outside the hotel, we’d walk down the line of taxis until we’d find one reluctantly willing to take us and the driver would always ask us why we’d want to go to such neighborhoods. In many ways, this was the “other America”, the one not often visible on television except perhaps in Action News crime reports. After visiting one school that served a primarily English as second language student body, we told the principal that the school probably wouldn’t work for the purpose of our film. He said that he understood and wanted to thank us for visiting his school anyway. He told us that we were the only journalists who had ever visited his school.  Many of the elementary schools we visited would have been appropriate settings for our documentary. That wasn’t our problem. The most difficult hurdle we faced in selecting a school was the apprehension of the principals when we described our filming plan. We would explain that we wanted to film over the course of an academic year and be able to work freely within the school in class rooms, halls, the playground and also be allowed to attend teacher-principal sessions. The concept was obviously a daunting one for the school principals to accept and we were usually told no with the easy excuse that our presence would be too much of a disruption to the school’s life. We were pretty much batting zero with our research efforts and very discouraged when we finally visited Stanton Elementary School. As soon as we walked in the door we got a good feeling. The school seemed orderly, bright and cheerful and had an obvious climate for learning. But the real prize was its principal Deanna Burney who didn’t flinch when we described our filming plan. Deanna was just a very special person, a documentary filmmaker’s dream, who understood the challenge of making a serious film about the plight of her students and welcomed the opportunity to help us. The question we’re most often asked about “I Am A Promise” is how we were able to film many of the scenes we did without the children being or appearing to be aware of the camera or distracted by it. Remember these were five to ten year old children. Working in our cinema vérité style, there is usually a kind of understanding between the subjects and the filmmakers that they are going about their normal lives and you are going to film them without them addressing the camera’s presence. With small children, it’s difficult if not impossible to establish those kinds of ground rules. Prior to I Am A Promise we had had years of experience working in the observational filming style so we learned to make our presence as low key and minimal as possible. This was the pre digital era, so we were shooting on 16mm film, all hand held using no lights. The Nagra sound recorder and Éclair NPR camera were our only pieces of equipment. It was just the two of us working with an assistant sound recordist. Also we did spend a lot of time at the school, which always helps as the children and teachers just got used to having us there. We’re very patient filmmakers and believe that reality will unfold if you wait long enough. We believe that one of the significant aspects of I Am A Promise is that it has a kind of unhappy ending. Though we certainly didn’t expect Deanna Burney, the school’s principal, to resign and get emotional at the end of the year, the fact that she does is a disturbing note to go out on. Audiences really felt her pain and understood that even with all of her energy, dedication and expertise it was not possible for her to single handedly overcome the complex problems involved in helping disadvantaged children in a school setting. Sadly the state of minority education in America hasn’t improved since the film won an Oscar in 1993. I Am A Promise is as relevant today as it was then. And we did eventually make that urban high school documentary albeit fifteen years later. Titled “Hard Times At Douglass High”, the film is a year in the life of the Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore." —Alan and Susan Raymond |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||